Article XII: U.S. v. Sioux Nation

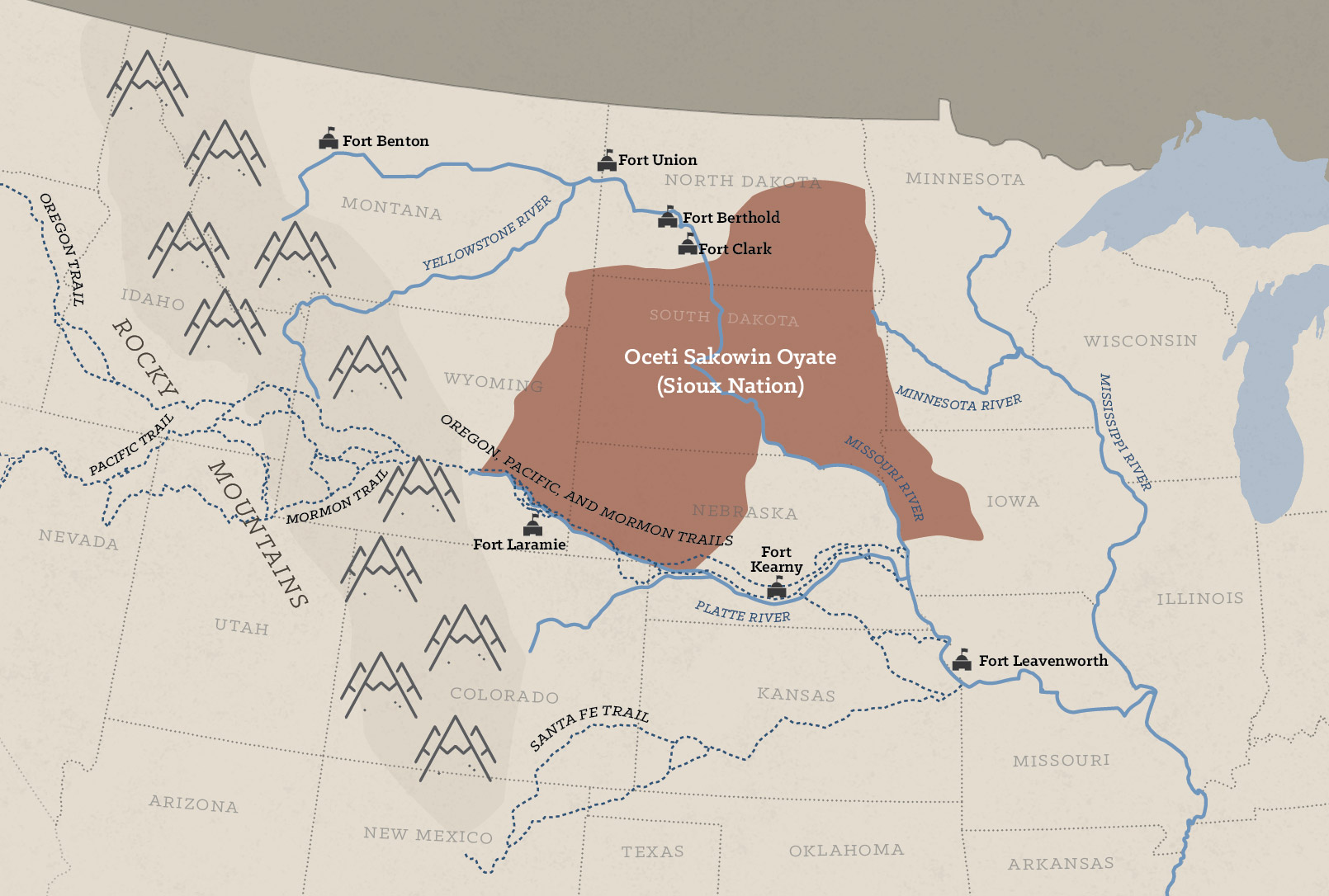

Print/Original“Under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the United States pledged that the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills, would be ‘set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ of the Sioux Nation (Sioux), and that no treaty for the cession of any part of the reservation would be valid as against the Sioux unless executed and signed by at least three-fourths of the adult male Sioux population. The treaty also reserved the Sioux right to hunt in certain unceded territories. Subsequently, in 1876, an ‘agreement’ presented to the Sioux by a special commission but signed by only ten percent of the adult male Sioux population, provided that the Sioux would relinquish their rights to the Black Hills and to hunt in the unceded territories, in exchange for subsistence rations for as long as they would be needed. In 1877, Congress passed an act (1877 Act) implementing this ‘agreement’ and thus, in effect, abrogated the Fort Laramie Treaty.”

Print/Paraphrased“Under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the United States pledged that the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills, would be ‘set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ of the Sioux Nation (Sioux), and that no treaty giving up any part of the reservation would be valid unless agreed to and signed by at least three-fourths of the adult male Sioux population. The treaty also guaranteed to the Sioux the right to hunt in certain territories outside the reservation. Yet later, in 1876, an ‘agreement’ presented to the Sioux by a special commission—but signed by only ten percent of the adult male Sioux population—stated that the Sioux would give up their rights to the Black Hills and to hunt in the off-reservation territories, in exchange for the minimum amount of food necessary to survive for as long as it would be needed. In 1877, Congress passed an act (1877 Act) that carried out this ‘agreement’ and, in effect, broke the Fort Laramie Treaty.”

View Original Version

View Paraphrased Version

United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. 371 (1980) No. 79-639. Argued: March 24, 1980 Decided: June 30, 1980

The court found that the 1877 Act was indeed a taking of tribal property. Taking implied an obligation on the U.S. government's part to make “just compensation” to the Sioux.